The proliferation of nuclear weapons as a form of hard power still remains one of the major security issues in today’s world. After the Cold War the international order underwent many changes, the most significant being the transition from a bipolar to multipolar system, which gave voice and space to new actors in the international arena, who now carry the ‘responsibility’ of sustaining the balance of power and world stability. However, the decentralization of power and creation of different centers of power created a more vulnerable and unstable system, with mistrust between those entities which constitute the international order growing over the past few years.

This essay approaches the international system as being within a context of total anarchy; so it takes a realist approach. This does not necessarily imply that the real world is chaotic and conflictual, but rather makes the premises that states are independent and sovereign, and furthermore that there is no higher power than the state itself. In the context of anarchy, states can be ‘dangerous’ to each other, but also do not inevitably act on bad intentions—rather in response to actions and circumstances that they might perceive as threatening. Under the premises of an anarchical world, states must ascertain strong positions in the geopolitical sphere in order to protect themselves.

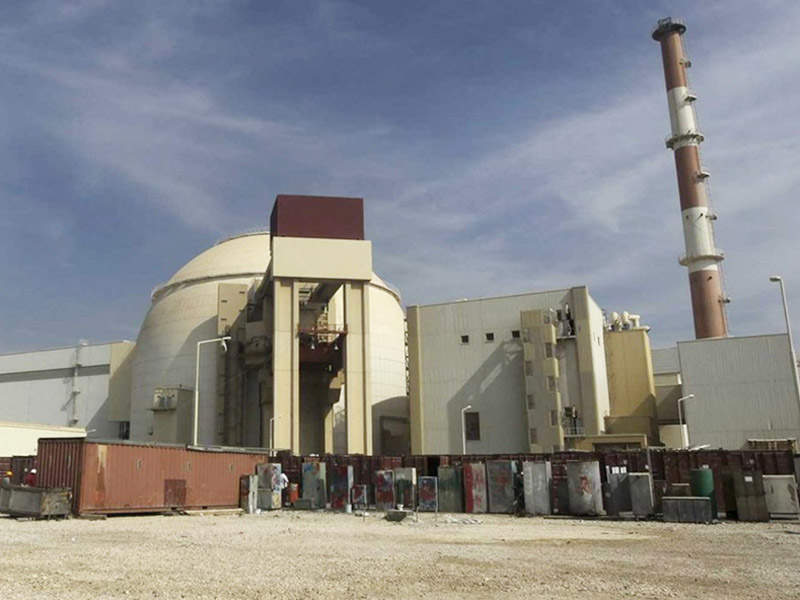

Consequently, their actions are the rational result of self-interest and the reliance on self-help. Due to the circumstances, a state tends to acquire ‘hard power’ for mainly two reasons. Firstly, to maintain a certain stability of power in the new multipolar system. Secondly, as a precautionary and defensive measure to protect itself, since—in an anarchical world order— other entities cannot be counted on. In order to have a better understanding of the importance of hard power in a multipolar system, this paper focuses on the particular case of Iran, which in the past decades has been aiming to acquire nuclear power.

The essay traces the theoretical reasons behind the interest of the Iranian state in acquiring nuclear power. Specifically, since the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Iran fell into a security dilemma and seemed to aim towards the re-building of the balance of power in the region of the Middle East—acquiring a strong position through the acquisition of hard power. Because of the contemporary multipolar and anarchical international system, the acquisition of hard power (in this case, nuclear weapons) by countries such as Iran has become one of the tools used to re-establish the balance of power.

From a realist standpoint, the state of nature of the international order is ‘anarchical;’ in which no actor can trust or have a previous knowledge of the true intention of the others; this system escalates into two main fundamental points. Firstly, according to Waltz, in an anarchical system “states balance rather than bandwagon,” in other words states are more concerned with their own relative power because in doing so they reduce the risk of allowing a hegemonic power to rise, an event which would threaten the security of the remaining countries. Furthermore they become the ‘balancers’ of the order in which they live, reinventing and maintaining the balance of power: a state of affairs in which no state is predominant over the other. However, with the advent of the nuclear weapons issue in the world politics, this balance of power has had to be reviewed by all entities of the international order. To a certain extent the fear of death and the fear of nuclear war have ‘obliged’ states to work for a common interest of peace, all the while maintaining the ‘realist competition’ with one another. As Hobbes, author of the Leviathon, would perceive, despite having a common purpose and a collaboration of superpowers, states are and will always be prepared to defend their own citizens and to ‘deter’ the other, and they will not count on others to accomplish their national security interests. Further, for neoclassical realists, all these ‘arrangements’ will be embraced automatically, since the balance of power is ‘imposed by external events’, and is a natural process.

In other words, if one country pursues the nuclear power, other states are likely to pursue the same power, in fear of allowing that state to rise as a hegemonic power. Secondly, since the state is sovereign, it must situate itself in a way that allows it to protect and sustain itself, as no other entity can be counted to do so, due to the mistrust inherent in the anarchical system. As Hobbes states: “Every sovereign hath the same right in procuring safety of his own people, that any particular man can have in procuring the safety of its own body”.

Therefore, the acquisition of hard power plays a significant role in the matters of national security, leading states into a relationship of dynamic of competitiveness with one another, based on the so-called security dilemma. The conditions of the security dilemma occur when an actor improves its national security by the means of hard power (such as the nuclear weapon), an act which is likely to be perceived by the others as aggressive and threatening. Moreover, this condition provokes counter-moves from other states. Explained by Sagan as “proliferation begets proliferation”, every time a state pursues nuclear weapons in an attempt to re-balance the power, it creates a nuclear threat to another state, which in turn will also wish to develop its own, for its own matters of security.

In the Iranian case, most of the policies are shaped by the political instability of the region, known as “questions of Persian Golf security” (Volker 2010, 95). With regards to its geopolitical condition, the country finds itself in between the two nuclear powers that are Pakistan and Israel. Moreover, its borders witness ongoing wars in countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan, wherein US troops are involved.

In addition, is well known that ‘bad’ and unreliable relations with western countries put Iran in a position of constant mistrust and self-help behavior. In fact, according to Volker, two types of policymakers can be observed in Tehran: those who have a little trust towards the West, and those who do not have any. Further, the country is seen as a rational actor that calculates its risks and opportunities with little interest towards the security of others, but rather with a large concern towards its own national security.

It is important to mention that—although US- Iranian relations have been mostly turbulent and insufficiently transparent—prior to the terrorist attacks of September 11 that shocked the world, Iran was already making efforts to pursue peace in the region, and even collaborating with the US to a certain extent. Iran supported the invasion of Afghanistan, and was collaborating with the United States in order to defeat the terrorist groups (such as the Taliban) in the region. In order to do so, Iran reinforced its border’s securities and agreed to apprehend Al-Qaeda fighters fleeing through its borders, as well as rescuing Americans near its borders. Nevertheless, the terrorist attacks on September 11 certainly marked a shift in how global security was perceived: it demonstrated how national borders were becoming fragile in the new multipolar and interdependent system. In other words, the attack re-emphasizes the importance of the state in its role of protecting its citizens. Indeed, as argued by B. Miller, after 9/11 the US changed to a more liberal offensive strategy—as manifested by the Bush Doctrine and the wars against Iraq and Afghanistan with the ensuing ramifications in the following years.

Indeed, the Iranian security dilemma was fueled by the claims of the Bush Administration, which portrayed Iran as a terrorist country, and part of the ‘axis of evil’ in the world. Consequently, Iran has two main reasons for pursuing nuclear power. Firstly, the country pursues a re-balancing of power in the region. As mentioned before, Iran finds itself in an unstable geopolitical position, and can re-stabilize the region by acquiring nuclear weapons.

As exemplified by Waltz, there is an analogy between historical rivals India and Pakistan: both acquired nuclear facilities. Both countries realized that a factor more dangerous than the adversary’s nuclear deterrent was the “instability produced by challenges to it,” and although ongoing tensions between the two remain present, they still maintain peace. According to Waltz, this condition could also apply in the Middle East. Secondly, the security dilemma in which Iran find itself plays a role in the inclination to pursue nuclear facilities. Although it is almost impossible to predict the actions of the state, it is likely—according to Waltz—that the aim of the country’s is in improving its own security and defensive capabilities, seeing as Iran has been ‘isolated’ in the international arena. Furthermore, considering the country a rational actor in an anarchical world, neither premises posed by Iran to justify the acquisition of nuclear facilities should be viewed as a threat, but rather as a natural re-shaping of the international order.

However, a common counterpoint to this idea (that reshaping the balance of power through state acquisition of nuclear weapons will bring stability to the international world order) is that acquisition instead deepens distrust and threat. According to a liberal perspective of International Relations, a state poses a threat to the international security when it acquires this kind of hard power, one which can only be contained through the formation of rivals and enemies. Indeed, despite his realist view of the world, Hobbes states that one of the major reasons for a state to go to war is the diffidence between states. Applying this theoretical framework to the Iranian case, the possible success of acquiring nuclear power could lead to a condition of security dilemma in other countries in the region, which will eventually create imbalances rather than a balance of powers. As commented by the Saudi media in 2006, Iranian acquisition of nuclear facilities “will make the region hostage to Iranian political conduct.” A parallel to this can be observed in East Asia, where North Korean possession of nuclear weapons has incentivized South Korea and Japan to improve their nuclear programs as well. Moreover, the act could also have domestic impacts, ones which would not benefit Iranian society. Indeed, the sanctions imposed on Iran by the US and its alliances are some of the most complex, and even harm the Iranian economy to a certain extent.

These sanctions have been ongoing since the Islamic Revolution in 1979, targeting one of the most important sectors of the Iranian economy: the energy sector. This then impedes the country from entering into the financial system. However, in 2013—with the election of the moderate president H. Rouhani—the US became open to finding cordial relations with Iran under certain conditions: the Islamic country limits its nuclear program. On this view, any continued Iranian pursuit of nuclear proliferation could isolate the country even more, and harm the domestic economy, which would put the legitimacy of the Iranian government in jeopardy. Further, seeing as “Atoms for peace and atoms for war are Siamese twins,” the proliferation of nuclear facilities in the multipolar order provokes different stand points as to whether it promotes stability or imbalance. Moreover, the significant changes in the distribution of power in the post Cold War and 9/11 international system have emphasized the importance of national security.

These events have deepened the distrust between nations, as well as giving them a larger share of responsibility when it comes to the maintenance of peace and balance of power. The Iranian case is an example showing that in this anarchical and multipolar order, national security is indeed becoming an important priority, with many countries falling into a condition of security dilemma. In addition, the Iranian case exemplifies one way of restoring the balance of power in the region: the acquisition of nuclear facilities. It is clear that hard power still plays a significant role in global affairs, however it is debatable whether it establishes a balance of power, or imposes distrust, threat and imbalance to the international system.